As floatplane pilots, we operate in a fluid environment. If you can excuse the pun, this is the most important facet of understanding water flying. Every takeoff and landing will be different than the previous, and we don’t have the luxury of ever becoming complacent. Everything is constantly changing, and we must be prepared at all times for any conditions presented to us. Wind, waves, wakes, debris, hidden obstacles, boaters, marine life, and power lines are just some of the things for which we need to be on the lookout. As you gain experience you will develop a keen eye for your surroundings, but until then, study this list of common mistakes so you can be as prepared as possible for your first seaplane flight.

1. Landing Flat

If you are coming from a land-plane background, flat landings aren’t the end of the world. You may bounce, go around, and try again. With seaplanes, flat landings can be catastrophic. As you touch down, the massive metal surface of your floats impacting the water creates an impressive amount of drag. A semi-flat landing feels a lot like landing with full brakes in a land-plane. Keep in mind that your sight picture will be different than you are accustomed to. A Cessna 172 on floats sits higher above the water than a wheeled Cessna 172 sits above the pavement. And while the difference may only be one or two feet, that can be enough to make you misjudge your height in the flare, or even touch down before initiating the flare. As you start your training, keep this in mind and err on the side of caution by keeping the nose higher than you would in a land-plane, until you have become familiar with the proper sight picture. Remember that with the higher nose attitude, you will experience greater drag forces and may need to use additional power to combat the sink.

Flat landings are more likely to occur in glassy water scenarios. Flat water can disorient the pilot, greatly affecting their depth perception. In addition, the flat water surface will result in higher drag on touchdown. To learn more about why that is, read our article on glassy water conditions here (you may be surprised to learn that glassy water landings have other applications besides when the water is reflective!).

2. Directional control on takeoff

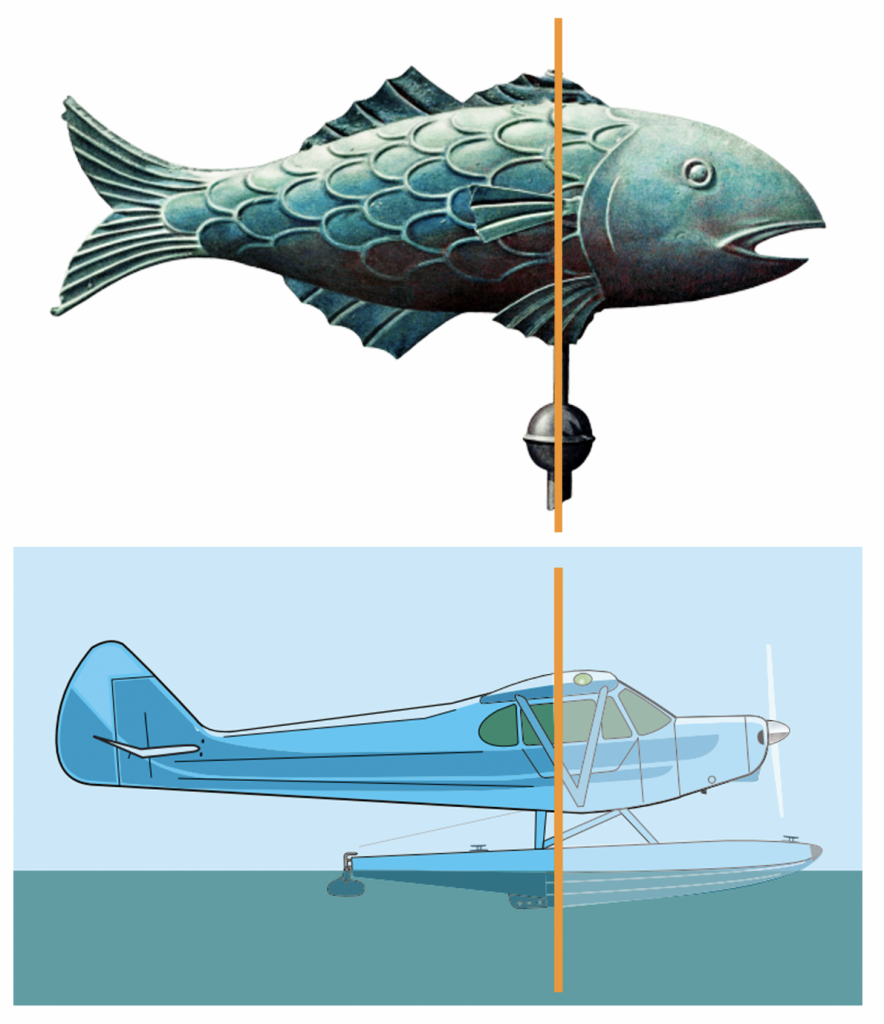

Floatplanes generally navigate on the water at what we call ‘idle taxi’, the slowest possible engine speed. Steering is accomplished using water rudders, which are connected to your air rudders or pedals via cables. When it comes time to takeoff, however, the water rudders are retracted and you are now at the mercy of the wind. Seaplanes have a very strong weathervane tendency, so if you aren’t pointed into the wind you will be soon! You may have read a lot about left-turning tendencies during your primary flight training, but it is possible that you haven’t truly experienced their effects. When you add takeoff power, several forces will start to work their magic, pulling your nose to the left.

If you are taking off with a left crosswind or quartering tailwind, you will experience the combined forces of left turning tendencies and weathervane tendency. These factors will make it very difficult, or even impossible, to maintain a straight heading through the takeoff run. To compensate for left-turning tendencies, try using full right rudder as you add takeoff power. As you settle down onto the step, remove right rudder as necessary to keep the airplane moving straight. Without runway markings, it can be difficult for beginners to sense yawing motions, so do yourself a favor and select a reference point on the far end of the lake to use as your imaginary center line.

To overcome weathervane tendency, you have two options. The first is to just take off into the wind, because that’s what the airplane wants to do anyway! If that is not an option, then you can over-compensate for the weather vane, allowing yourself time to pull up the rudders and add power. For more information, read our article on crosswind takeoffs here.

3. Landing on wakes

Depending on your flying background, there’s a decent chance you have encountered wake turbulence. And if you’ve encountered wake turbulence, then you most certainly know to respect it. Landing on water introduces a whole new type of wake: boat wakes! It may seem obvious… if I see a wake, then I won’t land on it. But it’s not that simple, unfortunately. Sometimes boat wakes can be obscured by wind waves, making them difficult to pick out as they mix.

Avoid boat wakes the same way you avoid wake turbulence: when you see a moving boat, trace its wake back to determine whether it crosses your desired landing path. Even if it looks like a small wake, it will 100% be larger than you thought once you’re up close. Just like airplanes, bigger boats make bigger wakes, and its the wake you don’t see that will hurt you the most. Never become complacent during a landing… continuously scan the area ahead to identify hidden wakes, floating logs, or maybe a friendly humpback whale preparing to breach. If it doesn’t look good add power to keep her flying until the water is better, or go around and start over.

4. Head down on taxi

Unlike a land-plane with brakes, once you cast off from the dock a seaplane is always moving. Unlike a typical land-plane airport with barbed wire fences and FOD removal, you will likely be sharing the lake with all sorts of occupants and debris. Therefore, looking outside is your number one priority at all times when operating on the water. If you prefer to use an iPad when flying, I would recommend keeping it stowed until you are at cruise, as it will only serve as a distraction on the water. In addition, using a checklist may cause you to divert your attention. Many seaplanes use placarded checklists at the top of the instrument panel so you don’t have to look down at all, but if your plane doesn’t have that, I would recommend holding the checklist up so you can continue scanning outside while you read. Practice your flows so you can do as much of the checklist as possible, only looking at it to confirm you didn’t miss anything.

This isn’t an excuse to not use checklists. For example, always make sure your water rudders are retracted for landing and takeoff. They can be easy to forget, even for extremely experienced folks like the pilot in the featured image of this article ;).

5. Porpoising and Skipping

When seaplanes are maneuvering on the step – whether during a step taxi, takeoff, or landing – there are two primary sensations you may feel in your quest for the ‘sweet spot’.

Porpoising most frequently occurs on takeoff when you do not have enough back pressure, a.k.a. the nose is too low. Porpoising can also occur when you have too much back pressure as you settle onto the step. This sensation feels like a rocking chair motion: forward and backward. The bows of the floats create little waves, then the float climbs over them, creating slightly bigger waves to climb over each time. If left unattended, porpoising will grow progressively worse, with each additional oscillation getting larger. To correct for porpoising, adjust back pressure to find your way back to the ‘sweet spot’. Memorize the sight picture of the ‘sweet spot’, so you will know whether you need to increase or reduce back pressure to stop the oscillations. If increasing back pressure doesn’t do the trick, pulling the power to idle and getting off the step may be your only option.

Skipping most frequently occurs when you add too much back pressure at a higher speed, a.k.a. the nose is too high. This oscillation usually occurs later in the takeoff run, or just after landing, as the seaplane moves across the water at a higher speed. The rear portion of the float is dragging too much in the water, resulting in a skip. This sensation feels like a bouncing motion, like a rock skipping on a lake: up and down. To correct for skipping, slightly reduce the back pressure until you find yourself back in the ‘sweet spot’.

For more information on porpoising and skipping, including the other scenarios in which they might pop up, read our article on the sweet spot here!

Leave a Reply