If there is one primary difference between seaplanes and land-planes, besides the obvious landing gear configurations, it is the extreme amount of drag we encounter moving through the water. Even some of the earliest seaplane designers understood that takeoff would be nearly impossible without reducing the amount of metal surface area contacting water.

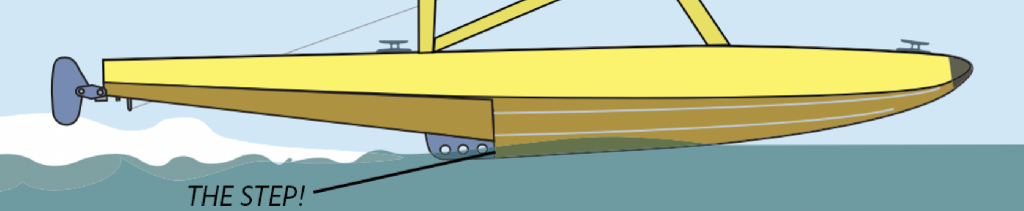

The solution was a design feature of the floats called the step. Instead of a single curving surface on the bottom of the float, there is a point at which the bottom surface abruptly shifts vertically – quite literally, a step. This feature disrupts the smooth water flow along the bottom of the float, enabling us to climb up and above the water surface, vastly reducing drag. When the seaplane is operating on the step, the majority of its surface isn’t touching the water at all.

Imagine a speed boat as it accelerates from idle to full speed. Its bow rises, and after a few seconds, the boat settles down to a planing attitude. Just like a speed boat, the seaplane nose rises, as you introduce takeoff power. The seaplane is now operating in the plow, pushing a wave of water forward under the bows of the floats. As it gains energy, the seaplane climbs up and over the bow wave, often referred to as the hump, settling down onto the step. Unlike most speed boats, we have elevator controls, allowing us to precisely position the nose to minimize drag.

With such a small fraction of our float touching water, precise pitch control is necessary to maintain a constant step attitude. This is the essence of the ‘sweet spot’ – the proper pitch attitude to minimize drag, with a very little amount of wiggle room. Too much back pressure, and drag will increase as the portion behind the step starts contacting water. Too little back pressure, and drag will increase as the portion in front of the step starts contacting water. At first, these drag forces may feel akin to tapping the brakes in a land-plane. If left uncorrected, or worsened by improper pitch inputs, these forces may result in pitch instability – oscillations like porpoising or skipping.

What is Porpoising, and How Do We Make it Stop?

Porpoising most frequently occurs on takeoff when you do not have enough back pressure, a.k.a. the nose is too low. Porpoising can also occur when you have too much back pressure as you climb over the hump onto the step. This sensation feels like a rocking chair motion: forward and backward. The bows of the floats create little waves, then the float climbs over them, creating slightly bigger waves to climb over each time. If left unattended, porpoising will grow progressively worse, with each additional oscillation getting larger. This is a form of dynamic pitch instability. To correct for porpoising, adjust back pressure to find your way back to the ‘sweet spot’. The FAA recommends to pull the power back to idle if you aren’t able to control the porpoising after the second oscillation. Memorize the sight picture of the ‘sweet spot’, so you will know whether you need to increase or reduce back pressure to stop the oscillations.

Porpoising might also occur after crossing a boat wake or localized swell. If the porpoise is strong enough to lift the plane out of the water, you are now flying at a speed potentially below the published stall speed of the aircraft. Never let the airplane stall, even if it means slamming back on the water. You may be forced to make a split decision whether to abort or commit the takeoff or landing. Be mindful of boat wakes, scanning the entire waterway to identify moving boats and their trailing wakes before landing. If you are planning multiple takeoffs and landings, land somewhere that will give you enough room to takeoff again without encountering any wakes. If you cross a boat wake later in the takeoff run, after the aircraft has accelerated significantly, your best option may be to commit to the takeoff and use the first wake to get you off the water. You must now use the rough water takeoff technique, remaining in ground effect as you accelerate to flying speed.

What is Skipping, and How Do We Make it Stop?

Skipping most frequently occurs when you add too much back pressure at a higher speed, a.k.a. the nose is too high. This oscillation usually occurs later in the takeoff run, or just after landing, as the seaplane moves across the water at a higher speed. It can also be caused by hitting a wake or localized swell at higher speeds. The rear portion of the float is dragging too much in the water, resulting in a skip. This sensation feels like a bouncing motion, like a stone skipping on a lake: up and down. To correct for skipping, slightly reduce the back pressure until you find yourself back in the ‘sweet spot’.

A common error for beginner floatplane pilots is to attempt to rotate the aircraft off the water, which often results in skipping. If you simply maintain the sweet spot attitude, the seaplane will naturally lift off the water when it is ready to fly. As you become more familiar with your seaplane, you may be able to introduce a slight rotation to takeoff earlier in rough water conditions.

Skipping is not a form of dynamic pitch instability like a porpoise, but the slamming force can be uncomfortable. Float planes aren’t built with shock absorbers, so we must be mindful to minimize slamming forces to protect the engine and airframe. Again, always scan takeoff and landing areas to identify boat wakes. Wait for the wake to pass, or takeoff/land in a different direction.

Summary

The mythical ‘sweet spot’ is actually a narrow range of pitch attitudes at which we minimize drag while maneuvering on the step. Finding the ‘sweet spot’ as a beginner floatplane pilot may take some trial and error. Become familiar with the sight picture and sensations of being too nose high or too nose low, as your familiarity will enable you to apply immediate corrections.

When operating on the step in glassy water conditions or downwind, the ‘sweet spot’ may be more difficult to dial in. Make small adjustments to correct for porpoising or skipping, and maintain the ‘sweet spot’ attitude until the airplane naturally flies off the water. Unless you are operating in rough water, attempting to rotate will likely just cause skipping and additional drag.

Leave a Reply