When you hear the term ‘glassy water’, odds are that it conjures an image in your mind of a calm water surface – so reflective, in fact, that it becomes difficult to differentiate the horizon with the water surface. And while these conditions are certainly glassy in its most literal sense, there are several other conditions in which glassy water techniques may apply. This article will dive into the characteristics of glassy water, in all its forms, as well as the proper techniques to apply on takeoff and landing.

Characteristics of Glassy Water

Glassy water is both flat and reflective, resulting in hindered depth perception and greater drag forces. If not done properly, glassy water can present some of the most hazardous conditions on landing. Even if your depth perception is only one or two feet off from reality, that can be enough to cause you to touch down before you are ready, thus, with a potentially improper touchdown attitude.

Another hazard is the flatness of the water surface. When water has texture, such as ripples or wavelets, the little air pockets between the chop reduce drag along the floats. Therefore, less of your float surface area is in direct contact with the water as it crosses the choppy surface. With flat, glassy water, there is very little air between the floats and the water, creating a sort of smothering effect. This is experienced as a noticeable drag force, and it can be strong enough to greatly impact takeoff performance. Additionally, touching down with a flat attitude will be punished by this increased drag – a feeling akin to landing with full brakes in a land-plane. If this force is strong enough (i.e. you touch down extremely flat), it can be enough to cause a dramatic pitching or yawing force, potentially flipping the plane over or resulting in a water loop.

Taking Off in Glassy Water Conditions

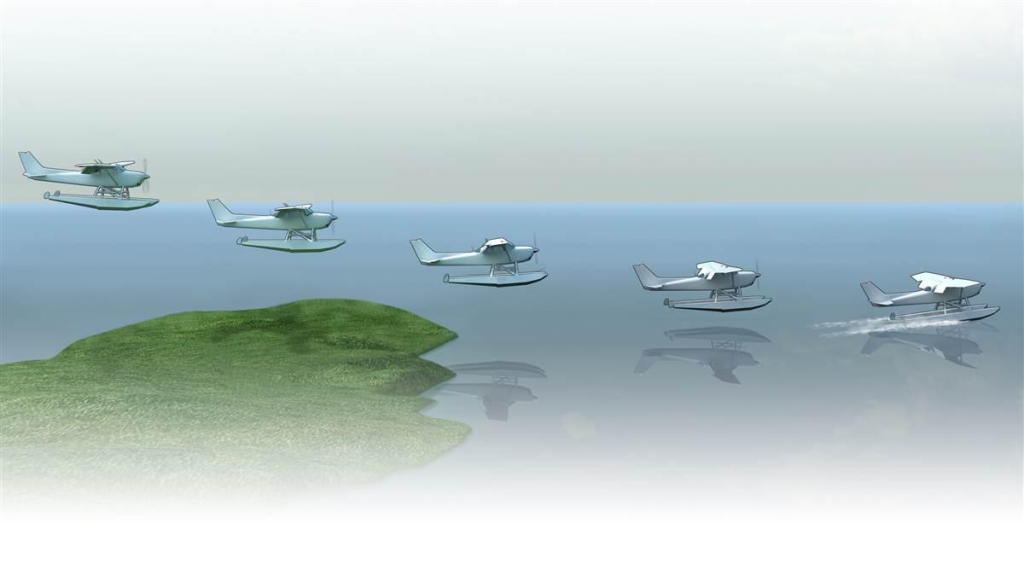

When taking off on glassy water, think DRAG DRAG DRAG! This drag force is so strong that it will require you to alter your technique to separate the plane from the water surface. As you introduce takeoff power, you will immediately notice that it is more difficult to get out of the plow and onto the step. Not only is the water creating a stronger drag moment, but the calm water surface is indicative of very light winds, which certainly isn’t helping your takeoff performance. The very act of getting the seaplane on the step is accomplished using lift, as you are technically lifting the plane up and out of the water. Lift increases as our waterspeed increases, which happens slower on glassy water.

Once you are on the step, the majority of your float has been lifted out of the water, minimizing drag. At this point in the takeoff run, it is essential to keep the seaplane in the ‘sweet spot’ – the pitch attitude at which drag is minimized. Pitch too high and you may experience skipping as the rears of the floats drag in the water. Pitch too low and you may experience porpoising as the bows of the floats dig in, resulting in increased drag and worsening pitch oscillations. It may be more difficult to find the ‘sweet spot’ on glassy water, as even the slightest incorrect pitch attitude may result in one of these forces, and even the slightest overcorrection will result in the opposite force.

Continuing on the step, you will feel the aircraft slowly accelerating toward takeoff speed. With time and experience, you will be able to recognize when the seaplane is almost ready to takeoff. As you get close to this point, introduce aileron deflection to roll the plane onto one float, lifting the other out of the water. As you do so, the drag will become centralized onto the float remaining in the water, resulting in a yawing force if left uncorrected. To compensate for this asymmetric drag, utilize opposite rudder to keep the seaplane moving straight. It is helpful to choose a reference point on the far end of the lake or waterway to use as an imaginary centerline, that way it will be obvious if you are veering one direction or the other.

Once you have successfully lifted one float out of the water, neutralize the ailerons so the rolling motion doesn’t increase any further, and as you lift fully off the water, reduce your rudder input until you are coordinated again. At this point, your number one priority is to stay coordinated and climb away from the water, as the lack of depth perception introduces the risk of inadvertently touching down again. Do not attempt to accelerate in ground effect.

It is a common mistake for beginner seaplane pilots to fixate on lifting a float out of the water, while allowing the pitch attitude to creep away from the sweet spot. If you allow the seaplane to skip or porpoise while attempting to lift a float, you are introducing additional drag and essentially negating the benefits of lifting a float. Another common mistake is waiting too long to lift a float, and lifting off the water before demonstrating this technique. As you learn the proper timing, it is fine to introduce the aileron roll too early, and if the float isn’t ready to lift, try again shortly after. To learn more about other common mistakes beginner seaplane pilots make, read our article on the topic here!

Landing in Glassy Water Conditions

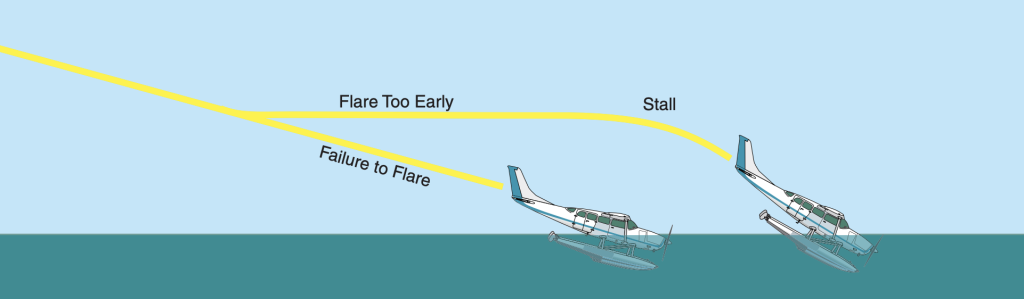

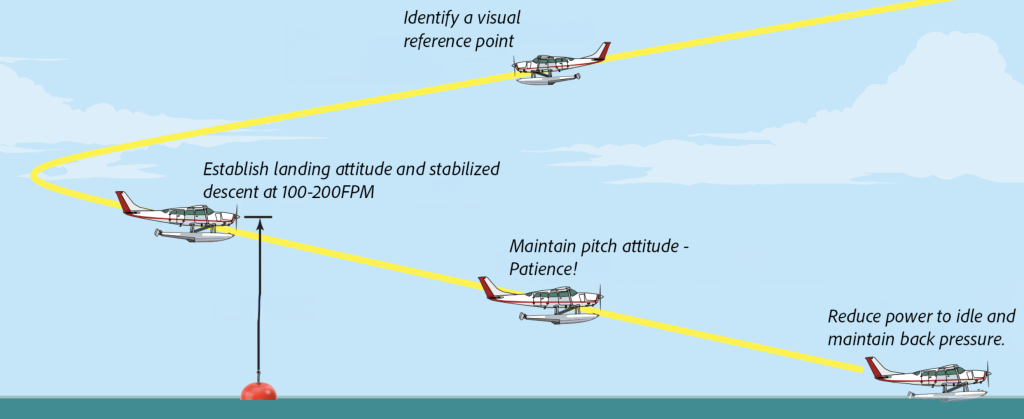

As you have learned, glassy water greatly impacts our depth perception and ability to judge height above the water. This makes it imperative to set up in the proper landing attitude before you lose visual references, so the airplane is ready to touchdown, whenever that occurs. Instructors will commonly teach students to transition to the landing attitude at 100 feet AGL and initiate a stable descent at 100-200FPM. This is great in the training environment, as it provides objective numbers and procedures to follow. This is also a completely satisfactory technique when you have plenty of water to work with, and known elevations and atmospheric pressure settings. However, if you are flying into a smaller mountainous lake, you may not know the exact elevation of the lake, or the atmospheric pressure conditions. Mountainous areas often have vastly different atmospheric pressures as you cross ridges and enter various drainages, so using your altimeter as a crutch for glassy landings can get you into trouble.

Whether you are coming in for your fifth glassy landing on a training flight, or exploring a new mountain lake, the best technique is to identify a satisfactory visual reference point. Use an object either in the water or on the shore to determine your height above the water, and transition to the landing attitude BEFORE you lose sight of it. If you are using an object on the shore, such as a tree, use it as a peripheral reference point. Once you lose sight of your visual reference point, assume that your depth perception is lying to you and touchdown is imminent. You can be creative with your reference point choice – a patch of seaweed, stumps in shallow water, a buoy, or even the trees on the shore. Regardless of which point you choose, descend as low as practicable before the point and transition to the landing attitude before you lose sight of it. If at any point you don’t feel comfortable descending visually any further, transition to the landing attitude and establish a stabilized descent. Once you have proceeded past the reference point, keep the landing attitude locked in like your life depends on it, adjusting power if necessary to maintain a steady descent. If you need to add or reduce power, adjust elevator pressure to maintain the pitch exactly where it was before you adjusted power.

The preferred descent rate for a glassy water landing is about 100FPM, though this number is not set in stone, and is bound to change as you encounter different conditions. For example, if you find yourself in a smaller lake, you may need to descend faster to get down before you run out of water. This brings me to another point – always give yourself as much room as possible. If you are flying in a sparsely populated area, approach from the side with shorter obstacles so you can get down closer to the water. If you are flying a standard traffic pattern, don’t turn base until you are all the way at the end of the lake, so you can minimize the amount of ‘wasted lake’. Let’s say you pass your visual reference point at 100′ AGL, and you have established a steady descent at 100FPM. If you are flying at 60 knots, it will take a full mile before you touchdown. If you adjust your descent rate to 200FPM, it will take only one half mile. A common saying used for glassy water landings is “pitch, power, patience”, as this maneuver can feel like it’s taking forever. Never try and force it down. Glassy landings are NEVER precision landings. Never try and land on a specific point… Take your time and exercise patience!

If you are running out of lake, it’s better to go around and set it up again, using what you learned from the first attempt. Thus, preflight planning and understanding your aircraft’s performance are paramount. Remember that FAR 91.103 requires pilots to become familiar with runway lengths at airports of intended use. Although the FAR specifically only mentions runways, a conservative interpretation of the regulation includes waterways as well. Modern tools make it very easy to measure lakes and assess obstacles, so there’s really no excuse!

Finally, when you eventually touch down, expect to be welcomed back to the water with a significant amount of drag. Hold on tight and keep applying back pressure until you have settled off the step and back to idle taxi. Continue using rudders throughout the entire landing run to maintain a straight path.

Other Conditions Which Warrant the Use of Glassy Water Technique

Glassy water landing technique should be used any time your depth perception is impacted by atmospheric conditions. This is not exclusive to calm, reflective water. Disorientation can occur under a flat, gray, overcast cloud layer, even if the water has texture. Whenever there is a sliver of doubt, err on the side of caution and apply glassy water techniques. In fact, it is in these gray conditions where I have scared myself the most, as I am misled into thinking I have adequate depth perception when I don’t. Therefore, I am always ready to transition to the landing attitude.

Another scenario which might call for the use of glassy water landing techniques is when there is a thin fog layer near the surface. Although it would certainly be best to land somewhere else, perhaps you found yourself cornered in by fog, and your only option is to land. More frequently, however, you will notice a thin fog layer that is perfectly transparent from above, until you find yourself looking horizontally through it on landing, and it has become fully opaque. If landing is your only option, you must use a glassy water landing technique. Given the conditions in which surface fog forms, odds are that the water is flat underneath. This is when it helps to be familiar with your aircraft’s performance. You should know the general airspeed at which you are established in the glassy landing attitude (but don’t use it as a crutch!).

Finally, landing into a sun glare may make it difficult to see the water ahead. Before beginning your approach, scan the water area from a different angle to assess the conditions and identify any potential hazards. Then, apply the glassy landing procedure. If the conditions allow, it may be better to accept a crosswind than to burn out your retinas!

Configuring the Seaplane for a Glassy Landing

In the absence of a POH recommending otherwise, it is best to approach glassy water landings with a reduced flap setting. If you have ever landed a land-plane without flaps, you have seen the high nose attitude that occurs during the flare. Landing with reduced flaps makes it easier for us to achieve the high nose attitude required for glassy water conditions, and is thus beneficial to us.

Flaps are both a lift and drag device. Without flaps, the wing is generating less lift, requiring a greater nose-up pitch to maintain level flight, and an even greater nose-up pitch to flare. Without flaps, the wing is also generating less drag, resulting in an increased speed at touchdown. Our goal is to touch down with a higher pitch attitude, but also a minimum waterspeed. The solution is to still use flaps, but at a reduced setting. In a Cessna 172 with 40° flaps, a final approach setting of 20° works quite well.

You will also want to configure for landing early in your approach, so the seaplane is completely setup and ready for landing once you pass your visual reference point.

Engine Failure Over Glassy Water

Losing an engine over glassy water is one of the most dangerous scenarios for a seaplane, as you will be forced to judge your height above the water to flare. Consider staying very close to the shoreline to optimize your chances of flaring at the proper altitude. Utilize your PIC authority to find the best spot for a safe landing.

Conclusion

While a perfectly calm day might be ideal flying conditions for a landplane, it presents a unique set of challenges for those of us on floaties. Respect the glass… all it takes is one ‘surprise’ flat landing to ruin your day.

If you enjoyed our content, please consider subscribing to our newsletter (coming soon)!

Leave a Reply