Seaplane training is a lot like a new airplane check-out. If you already have your private or commercial certificate, the FAA has already determined that you know how to fly an airplane. Thus, the primary training objectives of your ASES training will be to learn how to takeoff, land, and operate the seaplane on the water. Unlike land-planes, there are actually multiple methods for taxiing a seaplane. In this article we will discuss each of the seaplane taxiing methods, their proper techniques, and when to use them.

Idle Taxi

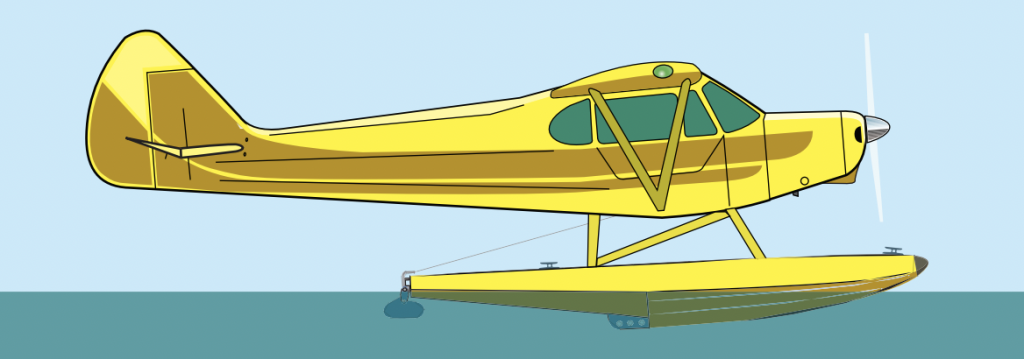

The most basic method to taxi a seaplane is at idle power. It is known as the idle taxi, or displacement taxi. When taxiing at idle, the seaplane sits flat in the water, with roughly the same attitude as when it is tied to a dock. This is the default taxiing method, as it has several benefits. Firstly, it provides for a slow and stable taxi speed, providing you with good water rudder authority and a tighter turning radius. Secondly, it reduces the chances of water spraying into the propeller, which causes significant damage. Maintain full elevator back pressure during idle taxi.

Plow Taxi

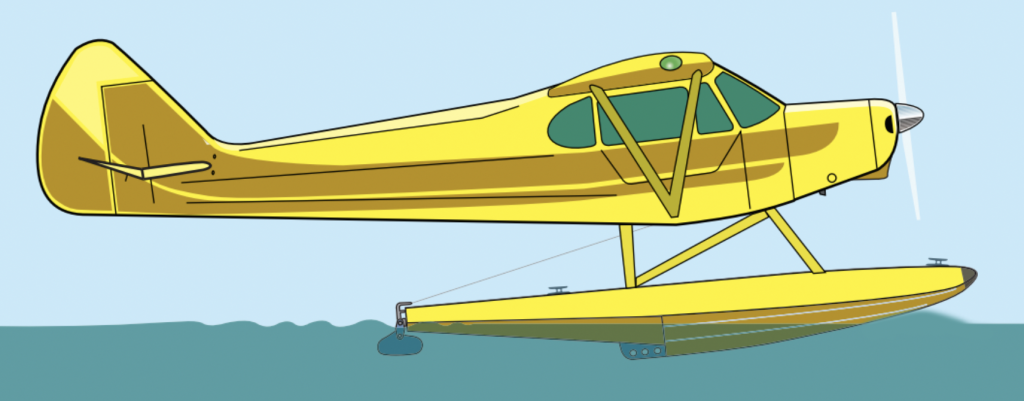

When operating in the plow the seaplane has a high nose pitch attitude and a higher speed than when taxiing at idle. Like a snow plow, you are pushing a wave of water ahead of the floats. You will most commonly experience the plow taxi during the engine run-up, though this taxiing method can also be used to turn out of a strong wind. While plow turns are an effective method for turning out of stronger winds, there are several risks associated with this technique. As the pitch attitude rises, the seaplane’s center of buoyancy shifts aft, reducing directional stability as the arm between the rudder and center of buoyancy shortens. If the center of buoyancy shifts far enough aft, it may result in reverse weathervaning, causing the seaplane to quickly turn out of the wind. This rapid yaw motion causes the outside wing to move faster. In addition, you will now be crossing the waves at an angle. Combine these factors with the high angle of attack of your nose attitude and you just may catch a stiff breeze under the outside wing, burying the inside float and capsizing the seaplane.

Other downsides to plow taxiing include a higher potential of propeller damage due to water spray, greater noise pollution, and reduced engine cooling. Maintain full elevator back pressure when taxiing in the plow to minimize the chances of spray damage to the propeller. The increased speed from operating at a higher power setting is partially offset by the higher water drag, so resist the temptation to taxi at power settings higher than ~1,000 RPM. For the sake of your seaplane training, never turn in the plow attitude. There are much safer methods for turning out of a strong wind, which will be discussed in this article.

Step Taxi

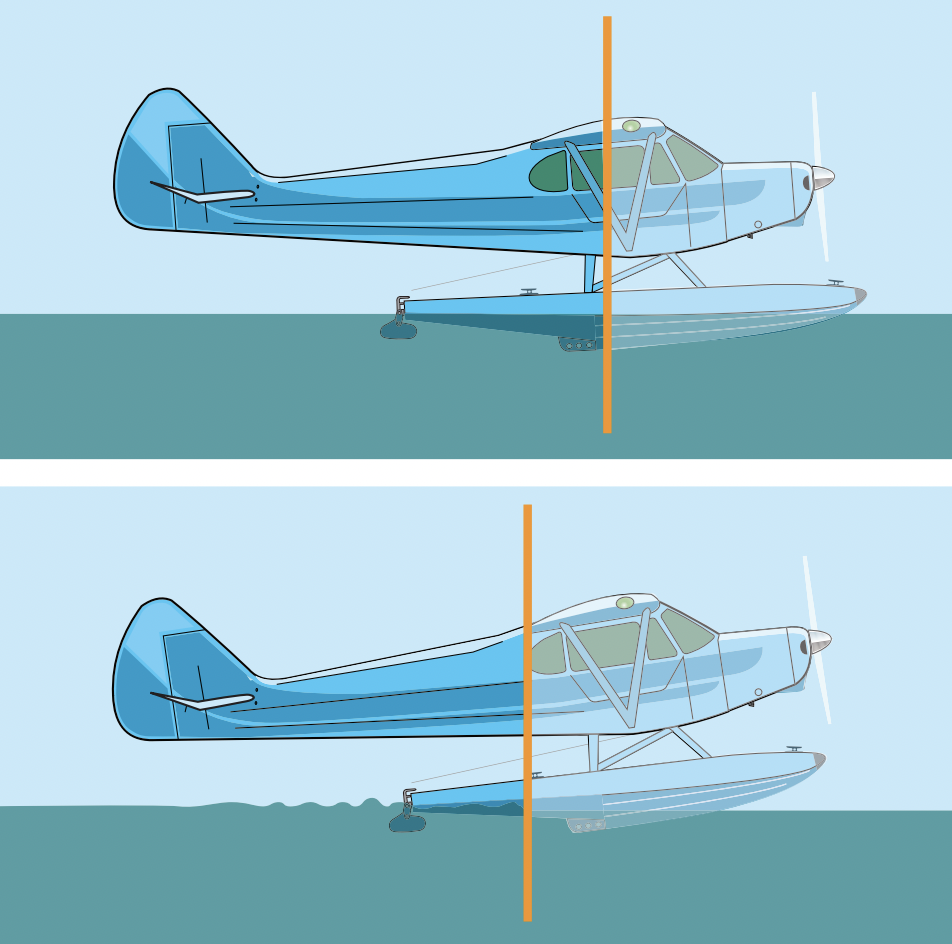

Arguably one of the funnest parts of flying seaplanes is operating on the step. Maintain full elevator back pressure while introducing full takeoff power, establish the step attitude, then reduce the power significantly. Find a power setting that allows you to maintain the step without accelerating or settling back down into the plow. If you find yourself accelerating, you may be moments away from takeoff, so reduce the power! If you find yourself settling off the step, add power. This sensation feels as though the water is pulling you down, so continue adding power until you feel the seaplane riding on top of the surface again, but not accelerating toward takeoff speed. While it is helpful to take note of the step taxi power setting for your particular seaplane, this number may change depending on the day’s conditions, such as higher density altitude, wind, or a glassy surface. I configure the seaplane with takeoff flaps, as that helps me get onto the step and eliminates the need for additional configuration changes before takeoff. Once established on the step and at a reduced power setting, you can introduce rudder to turn in either direction. Some instructors teach the use of ailerons in the direction of your turn, but I have found that their impact is very minor and unnecessary.

Step taxiing is most commonly used in the confined area takeoff technique, but it can also be used if you landed well short of your destination and would like to get their quicker! When turning on the step, make sure to keep your eyes forward to ensure you are maintaining pitch attitude in the sweet spot. You can safely make tight step turns, even introducing power into the turn, as long as you keep your pitch attitude in the sweet spot. You will generally be able to turn right more aggressively than you can turn left, as you are working against the natural left-turning tendencies.

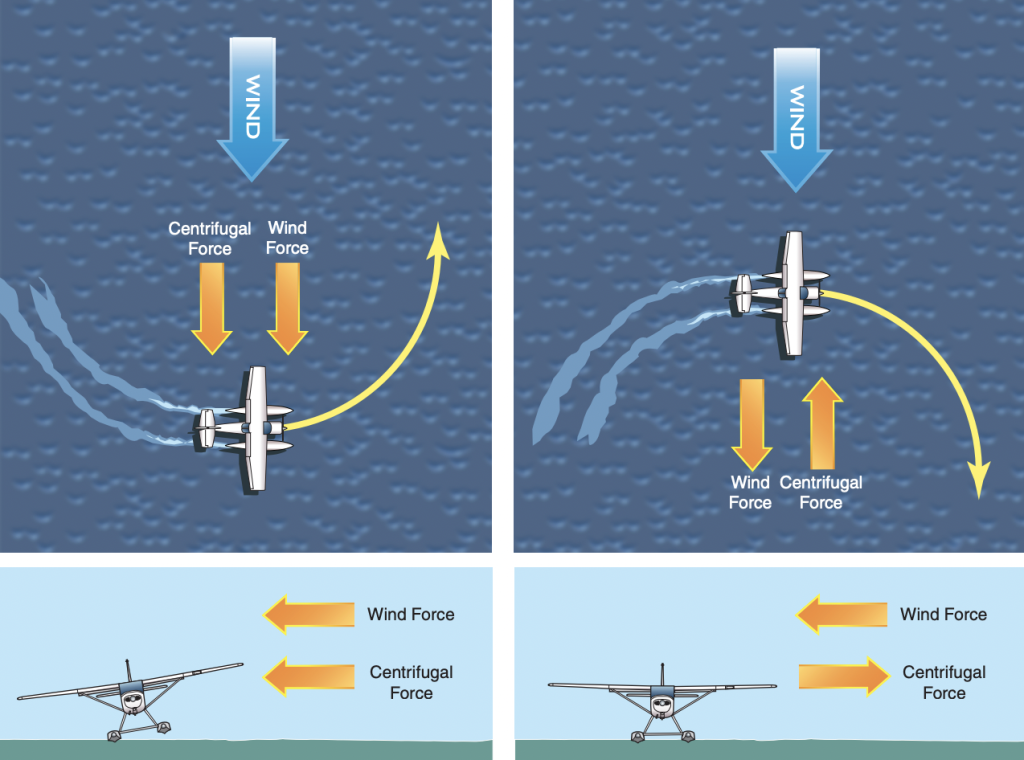

The primary hazards of step turns are losing the proper pitch attitude, thus allowing the floats to dig unevenly, as well as turning from a downwind to upwind heading. As you turn away from a downwind heading, the centrifugal force is acting in the same direction of the wind, introducing the risk of flipping over. Turning from an upwind to a downwind heading has the opposite effect, with centrifugal force and wind counteracting each other. Never turn from a downwind to an upwind heading while operating on the step, unless the winds are calm. If you feel a float digging or a wing rising during a step turn, apply opposite rudder and reduce power to idle to settle off the step.

Momentum Turns

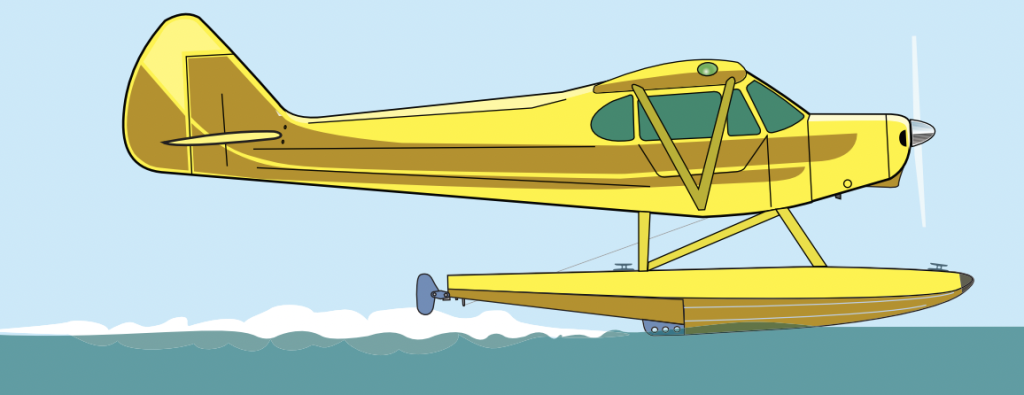

If you find yourself in very windy conditions, you may have difficulty turning to a downwind heading. Seaplanes have extremely positive directional stability on the water, manifested primarily in their weathervaning tendency. As you turn out of the wind, you expose a great deal of side surface area to the wind. Since the majority of that surface area is located behind your center of buoyancy, the tail is pushed until it is aligned back with the wind. Some seaplanes have additional vertical tails or fins to provide greater directional stability in the air, resulting in an even stronger weathervaning tendency on the water. When you find yourself unable to turn out of the wind, you have several options. Your first instinct might be to add power and force the seaplane to turn, which is undesirable as it places it into the unstable plow attitude.

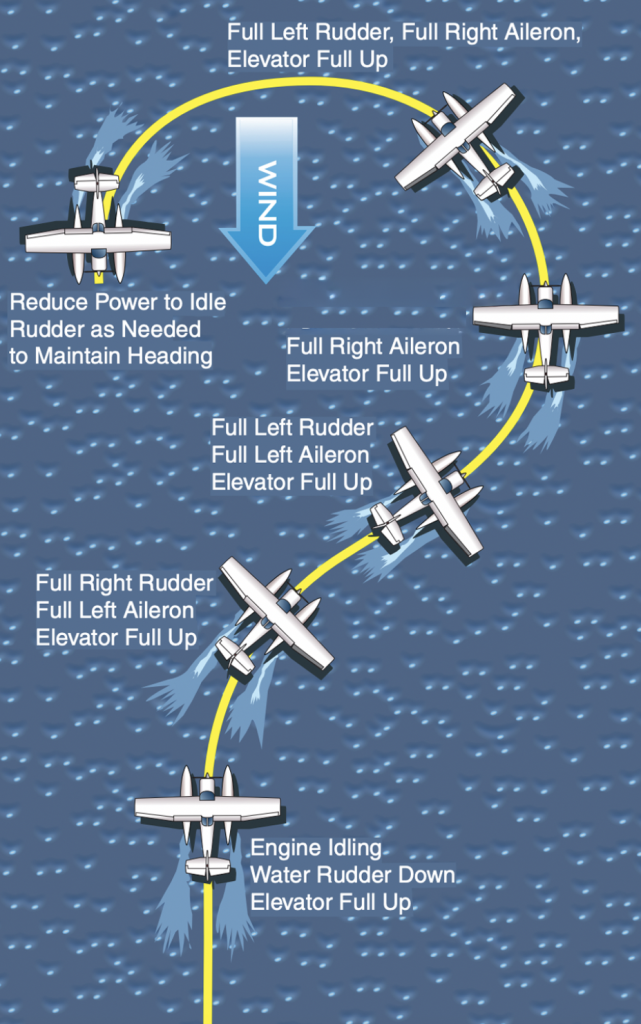

Instead, initiate a momentum turn. While operating at idle power, turn as far right as you can, correcting for the crosswind with ailerons. Once the weathervaning force stops your turn, introduce full left rudder, allowing the seaplane to turn back into the wind. As you pass through the upwind heading, switch your aileron correction and maintain full left rudder. Keep your eyes straight ahead to judge the momentum of your turn, adding a very small burst of power if the turn rate starts to decrease. If you make it past the 90° point, switch the aileron correction one more time for the quartering tailwind. If the turn grinds to a halt, simply initiate a momentum turn in the opposite direction.

You may need to attempt multiple momentum turns back to back before you make it all the way around. Once you do make it to the downwind heading, dance on the rudders to keep it going perfectly straight, directly downwind. Choose a good reference on the shore so you can identify and counteract any yaw. If you expose even the slightest amount of side surface area, it may be enough to force the seaplane all the way back around into the wind. Be patient with this maneuver. Whether through gained momentum, or a lucky break in the wind, I have successfully turned downwind using a momentum turn after 5+ failed attempts. If it’s truly not working, your next best option is to sail.

Sailing

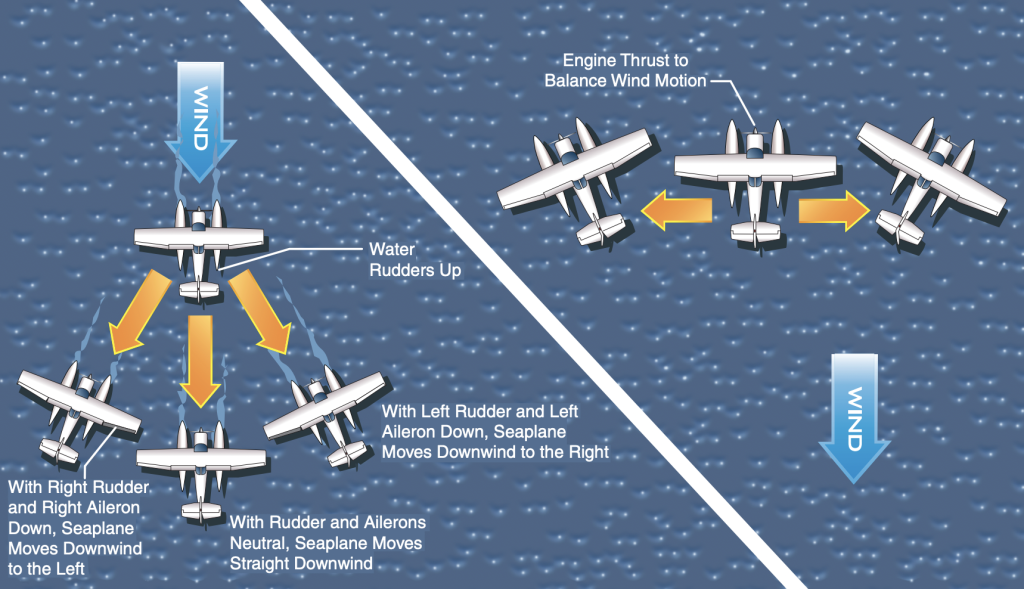

When all else fails, sailing is a great method to get from Point A to Point B. Sailing is accomplished by lifting the water rudders and allowing the wind to push the seaplane backwards. In most scenarios, you will need to shut off the engine, as idle power is enough to keep you moving forward in all but extreme wind conditions. With the water rudders up, simply point the nose in the opposite direction of where you want to go, and correct for the crosswind with ailerons. If it helps you visualize it better, point the ailerons where you want to go and use opposite rudder. You will now be moving backwards at a very shallow angle, moving very slowly through the water. To gain speed, open the doors to expose additional surface area to the wind. Some instructors and handbooks suggest putting the flaps all the way down, but that will block your rearward vision, so don’t do that! To uninitiated onlookers, it may appear that you are in distress, so rearward vision is of the utmost importance!

If it is extremely windy, you may be able to sail with the engine running. In these conditions, the seaplane is actually very maneuverable! Retract the water rudders and adjust power to move forward, side to side, or backwards.

Sailing is useful when it is too windy to turn to a downwind heading, or when beaching with an onshore wind (wind blowing from the sea toward the beach). You can also alternate between power-off sailing and idle taxi techniques to zig-zag your way into a confined dock area.

Conclusion

Throughout your seaplane training and career you will use each and every one of these five taxiing methods. While taxiing a land-plane is generally straightforward, maneuvering a seaplane on the water introduces several new challenges and considerations. Although you may not experience wind strong enough to require momentum turns or sailing during your training, be prepared to explain each of these methods during the oral portion of the checkride. And when you DO find yourself in those scenarios, remember what you learned and apply the proper technique. Most importantly, never try a plow turn in high winds, or a step turn from a downwind to upwind heading!

Leave a Reply